The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck, USA, 1939

Burn coffee for fuel in the ships. Burn corn to keep warm, it makes a hot fire. Dump potatoes in the rivers and place guards along the banks to keep the hungry people from fishing them out. Slaughter the pigs and bury them, and let the putrescence drip down into the earth (…); in the eyes of the hungry there is a growing wrath. In the souls of the people the grapes of wrath are filling and growing heavy, growing heavy for the vintage.(533)

Although the formation of the Dust Bowl can be traced back to the elimination of the Indians and the blind ignorance of the new settlers, it was greed that finally exacerbated the situation. And it was this combination of ignorance and greed that drove hundreds of thousands of small farmers westwards into California where the same greed and rapacity existed but with new names and new faces.

Steinbeck’s classic at more than 600 pages is not a one-night read, but it is an easy, if often troubling, read. The voices are the voices of the people who have lost their land and their right to the most basic essentials of life. They have become non-people, vermin, scum; and when they attempt to fight for better conditions they are labelled ‘reds’. Ordinary, otherwise decent, citizens see the migrants in their dirty makeshift camps, and they listen to the greedy, controlling few and they nod their heads when they hear the words ‘reds’ and ‘agitators’. Their fear takes over, and like many people even today, they side with the indulged and the powerful, not necessarily because they agree (in many cases they have little understanding of the situation), but because they are scared. Suspicion of the hungry, filthy, homeless people has been planted in them by the few, and the otherwise decent citizens tell themselves that they have to protect themselves, their families, their jobs and their right to a decent life.

The Grapes of Wrath focuses on the Joad family, their forced eviction from the family farm, as the large land holders and tractors move in, and their painful journey from Oklahoma to California. It looks at their optimism and their despair while putting forward the observation that alone each of us is weak but together we can do great things.

One man, one family driven from the land (…) I lost my land, a single tractor took my land. I am alone and I am bewildered. And in the night one family camps in a ditch and another family pulls in and the tents come out. The two men squat on their hams and the women and children listen. Here is the node, you who hate change and fear revolution. Keep these two squatting men apart; make them hate, fear, suspect each other. Here is the anlage of the thing you fear. This is the zygote. For here “I lost my land” is changed; a cell is split and from its splitting grows the thing you hate―”We lost our land.” The danger is here, for two men are not as lonely and perplexed as one. (260)

I feel that the central figure in the book is Ma. She is the entity that holds the family together; without her the Joad family would have ceased to exist. In spite of her own fears and sorrows, she supports, feeds, advises and comforts.

Ma was heavy, but not fat; thick with child-bearing and work. She wore a loose Mother Hubbard of gray cloth in which there had once been colored flowers, but the color was washed out now, so that the small flowered pattern was only a little lighter gray than the background. The dress came down to her ankles, and her strong, broad, bare feet moved quickly and deftly over the floor. Her thin, steel-gray hair was gathered in a sparse wispy knot at the back of her head. Strong, freckled arms were bare to the elbow, and her hands were chubby and delicate, like those of a plump little girl. She looked out into the sunshine. Her full face was not soft; it was controlled, kindly. Her hazel eyes seemed to have experienced all possible tragedy and to have mounted pain and suffering like steps into a high calm and a superhuman understanding. She seemed to know, to accept, to welcome her position, the citadel of the family, the strong place that could not be taken. And since old Tom and the children could not know hurt or fear unless she acknowledged hurt and fear, she had practiced denying them in herself. And since, when a joyful thing happened, they looked to see whether joy was on her, it was her habit to build up laughter out of inadequate materials. But better than joy was calm. Imperturbability could be depended upon. And from her great and humble position in the family she had taken dignity and a clean calm beauty. From her position as healer, her hands had grown sure and cool and quiet; from her position as arbiter she had become as remote and faultless in judgment as a goddess. She seemed to know that if she swayed the family shook, and if she ever really deeply wavered or despaired the family would fall, the family will to function would be gone. (153-154)

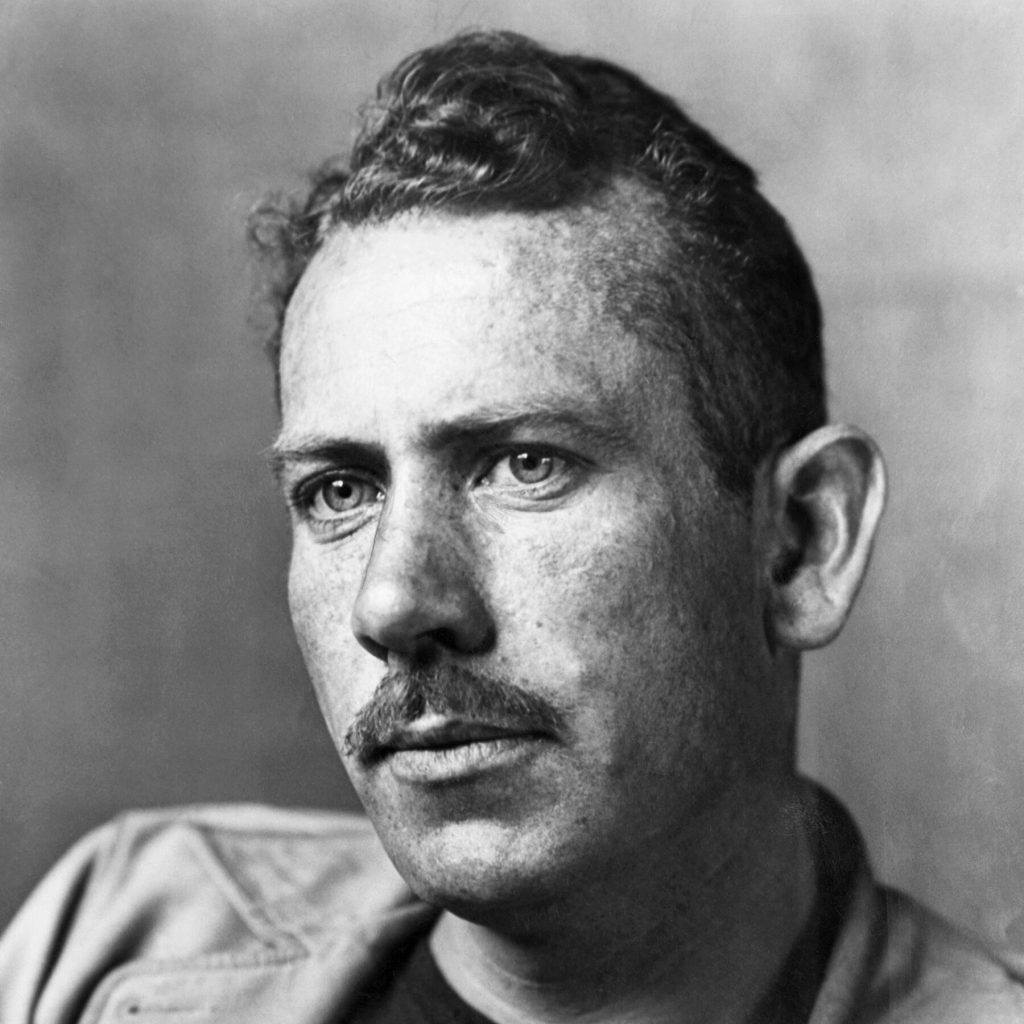

The understanding that the many, working as one, have power over the few (the basis of the Union movement), runs as a red thread through the book. The migrant situation in California concerned Steinbeck greatly, and he noted that The Grapes of Wrath was a book that had to be written. He was not interested in writing a popular book; he wanted to ‘rip a reader’s nerves to rags’ (Conversation with Pascal Covici January 16 1939). In spite of, or perhaps because of, what he may have wanted, The Grapes of Wrath has sold more than 14,000,000 copies as well as winning both the Pulitzer Prize (1940) and the Nobel Prize (1962).

It is a book that one absorbs without effort, similar to breathing. It is not only the content but also the structure – descriptions of the Joads’ odyssey, heavily reliant on what seems to be realistic dialogue, interspersed with beautifully written background chapters – that makes the book both compelling and completely unforgettable.