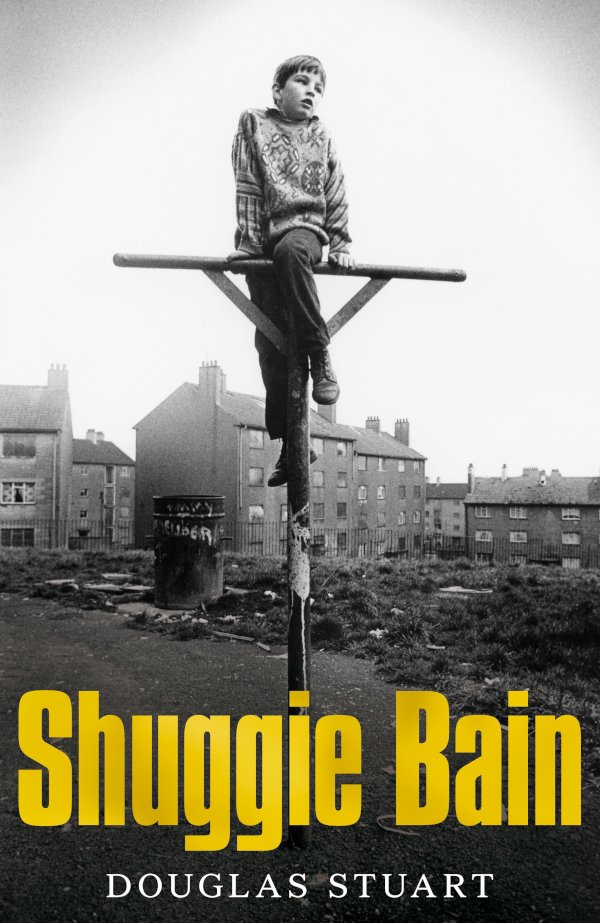

Shuggie Bain, Douglas Stuart, UK, 2020

Raw, real, depressing and beautifully written, Shuggie Bain, centres on a working-class family in Glasgow between the early 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s. It is an unedited picture of poverty and alcohol abuse, showing how the two things fuse together to eventually both direct and change people’s lives. Many of the people filling the background of this wonderful book are victims, directly or indirectly, of radical decisions made by the Thatcher government. Having been cast aside, without employment and without a future, these people focus their hopes on merely surviving – for one more day; for one more week.

Raw, real, depressing and beautifully written, Shuggie Bain, centres on a working-class family in Glasgow between the early 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s. It is an unedited picture of poverty and alcohol abuse, showing how the two things fuse together to eventually both direct and change people’s lives. Many of the people filling the background of this wonderful book are victims, directly or indirectly, of radical decisions made by the Thatcher government. Having been cast aside, without employment and without a future, these people focus their hopes on merely surviving – for one more day; for one more week.

Shuggie (Hugh) is the youngest child of Agnes. He has an older half-sister and half-brother from Agnes’ first marriage to a Catholic. Agnes, however, is hoping to improve her lot, and when Protestant Shug arrives on the scene, she ups and leaves her husband. She had expected to ‘move in’ with Shug, but it turns out that Shug (who has left his wife and four children) has a taxi, a penchant for young women and not much more. Agnes’ parents have a small council flat in a high-rise, and it is here that Agnes, Shug and the children find temporary accommodation, which stretches out to permanent accommodation. Then, after several years and completely ‘out of the blue’, Shug tells Agnes that he has found a house for them – a house with three bedrooms and a garden.

But Shug has no intention of settling down with Agnes and the children, and once he has moved them into the house, he disappears with a new girlfriend. Agnes is now on her own with three children in a mould-infested house in an ugly, dying mining town on the edge of Glasgow, where gossip and malice is all there is to sustain many of the inhabitants. An outsider, she slowly commences her downward spiral into alcoholism. Her two older children eventually leave, one after the other, but Shuggie, sensitive, particular and ‘different’, remains, hopeful that he will be able to save his mother, whom he loves more than anything else in the world. His efforts, selfless and heartbreaking, are, however, doomed from the start. When we meet him at the beginning of the book, he is a reasonably optimistic five-year-old; when we finally leave him, he is seventeen, wiser and probably less optimistic, trying to juggle the very few meagre opportunities that life has given him.

Not a fan of books filled with dialogue, I nevertheless found that Stuart’s use of the Glaswegian and other Scottish dialects, as a central part of the book, gave a strong feeling of place, culture, attitudes and even religion. Those of us who are not from Scotland may not understand every single word, but that is of no real concern: it is what is behind the words that matters, and these emotions are impossible to miss.

This is a book, which gives us cause for thought as well as many reasons to be angry, sad and frustrated with people in general and politics in particular. It is also a book that manages to illuminate the good that is a part of most people but which is not always evident. Definitely a worthy winner of the 2020 Booker Prize.

You may enjoy listening to an interview with Douglas Stuart.