Diane’s Newsletter 19th March

I will be publishing The Waiting Room in May.

The Waiting Room began life as an interim novel while I was working on another novel with an historical background. About twelve months ago, I decided I needed a break from the more demanding novel, and I began The Waiting Room. From the beginning, I had expected it to take about three months, but it had other ideas, and the three months soon became six, and the six then became nine…

The initial idea for The Waiting Room came from an observation that there are many people nowadays who are so focused on themselves that they do not seem to care about what is actually happening around them – as long as their own basic comforts remain intact then everything is obviously (as far as they are concerned) going to be all right. My thoughts moved around in different directions and eventually focused on perspective. As we all know, we can look at the same thing but see and understand it differently. What we see around us, how we act, and how we relate to others depends to a great deal on our interpretation of that which we see and/or believe is going on around us.

This is not a novel for action lovers – the suspense is more psychological than physical. The Waiting Room may not have all the answers neatly packaged, but it will throw out a lot of questions, and it will, hopefully, provoke thought. If it manages to do that, then, as far as I am concerned, it will have succeeded.

I will be giving away six advance copies of the book in the next Newsletter, 16th April. There you will find all the information you need plus a link to participate in the giveaway. If you are in interested in receiving a free copy, keep this date in mind, and don’t forget to open the Newsletter when it arrives in your in-box.

According to Wikipedia, Crocus is a genus of perennial flowers in the Iris family, growing from bulbs, and mostly cultivated for the cute looking flowers that bloom in winter, spring, and autumn. The name comes from the Greek word κρόκος (krokos), which was probably borrowed from a Semitic Language (Hebrew → karkōm; Aramaic → kurkama; Arabic → kurkum). Kurkum, in Arabic, means saffron, a widespread spice that is obtained from the stigmas of a species of Crocus called Crocus Stativus, that blooms in Autumn.

The Crocus is a cup-shaped flower, that can be found in a variety of colours (purple, blue, yellow, and white are most common), and it has three stamens. The Crocus has a “look-alike sister”, the Colchicum, a toxic plant that has six stamens, which is often referred to as the Autumn Crocus. The two species can be easily confused by the casual observer.

There are a lot of legends surrounding this delicate flower, but there is one in particular that I like. Ion Ghinoiu, a Romanian author, who writes mostly about Romanian mythology, traditions and customs, wrote in the book Days and Myths (Zile și Mituri), about two beautiful sisters, named Spring Crocus (Brândușa de Primăvară), and Autumn Crocus (Brândușa de Toamnă) – Brândușa (Crocus) is a common Romanian female name. According to Ghinoiu’s story, the two sisters were banished, by their step mother, into the forest. One of them was sent away in early Spring, and the other one in late Autumn. The Gods felt sorry for their sorrow, and turned them into flowers. One that blooms in Spring, and one that blooms in Autumn. Since then, they have been trying to find each other, but without success. It is said that the person who braids both flowers into a wreath, for the Crocuses to forget their longing, and releases it onto water, does a good deed for which they will receive atonement.

Cristina

I recently read a book about a ferry cruise between Sweden and Finland. The first part of the book captured my attention with its colourful descriptions of a number of the people on the ferry – some intent on having a couple of days of fun; some attempting to run away from situations they cannot change. I was interested to see how these different people would intertwine with each other, and I anticipated that I would probably enjoy the book.

I recently read a book about a ferry cruise between Sweden and Finland. The first part of the book captured my attention with its colourful descriptions of a number of the people on the ferry – some intent on having a couple of days of fun; some attempting to run away from situations they cannot change. I was interested to see how these different people would intertwine with each other, and I anticipated that I would probably enjoy the book.

Then, about a third of the way through the four-hundred-plus page book, two vampires are introduced into the mix, and the story, and my expectations, changed dramatically. Fans of vampire literature will most probably enjoy the book – the reviews seem to say as much – but, for me, the book was a disappointment.

I did, however, finish reading it (which says more about me than the book), and I then began to wonder about these things called vampires. Where did the superstition come from? How long have people been believing in vampires? Is there anything that connects the nightmare to some kind of reality?

What I discovered is that the idea of vampires has been around for centuries. It may have evolved because of people’s ignorance of what happens to a body after death, together with a fear of the dead contaminating the living. When it was noted that hair and nails continued to grow on a corpse, it was assumed that the corpse was still ‘living’. This assumption was strengthened when a dark, blood-like fluid (caused by the break-down of the inner organs) ran from the corpse’s mouth, making people believe that the corpse had been ‘feeding’ on the life-force of the living, that is to say, blood. In some places, it was believed that people who had been accused of being witches, when alive, became vampires after death.

The superstitions gained traction during disease epidemics, or when neighbouring animals died without explanation. Stones were often placed in the mouth of the dead to stop the corpse from ‘feeding’. The corpse could also be pierced with a metal rod or a wooden stake. As far as the living were concerned, they were being tormented from beyond the grave, and they had to do all they could to stop the torment. Many everyday objects were seen as having special protective powers: garlic, mustard seeds, a crucifix, holy water, mirrors…

In the eighteenth century, there was a resurgence of this belief in vampires, in spite of both Pope Benedict XIV and Maria Theresa slamming the belief as superstition and fantasy. But the ire of Benedict and Maria Theresa did little to change the situation. If someone died (usually of an illness), and a relative or a neighbour then also sickened, it was often assumed that the person who had died first was ‘feeding’ on the living. In such cases, the corpse would be exhumed, the heart would be removed and reduced to ashes. The ashes would then be mixed into a potion for the sick person to drink. This was supposed to cure the ailing person, but more often than not it simply hastened his or her unhappy end.

The nineteenth century saw a new kind of vampire being described in books like The Vampyre and Dracula. These vampires were usually aristocratic, often lived in castles, and had strong sexual needs. They still depended on blood for nourishment and spent much time looking more dead than alive, but they usually also had powers of attraction that were completely absent in the earlier vampires.

Fast forward to the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and we find that the vampire has found its place not only in literature but also on the screen. The modern-day vampire seems to be a mixture of all that has gone before with a bit more thrown in for good measure. Vampires can now be young, old, zombie-like, devoid of communication skills, ugly, handsome/beautiful, urbane, intelligent…

Fast forward to the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and we find that the vampire has found its place not only in literature but also on the screen. The modern-day vampire seems to be a mixture of all that has gone before with a bit more thrown in for good measure. Vampires can now be young, old, zombie-like, devoid of communication skills, ugly, handsome/beautiful, urbane, intelligent…

It may be interesting to note, according to wikipedia, that a physics professor did a calculation in 2006, arguing that it is mathematically impossible for vampires to exist. He worked out that if vampire number one were to have made his or her appearance in January 1600 and then fed once a month, with each victim in turn becoming a vampire, it would have taken no more than two and a half years before the entire world’s population (1600) would have consisted of only vampires.

For those of you who are interested in vampire stories, the book I read was Färjan by Mats Strandberg. It is called Blood Cruise in the English translation.

Images from wikipedia, wikimedia, flickr and India Today

March = 3, and 3 (at least according to numerology) = creativity and self-expression. 3 is a social, friendly, fun-loving number; it has a need to be optimistic; it is often attracted by glitter and ornamentation. It is usually good with words, and if I were to choose one word to describe it I would choose expressive.

March = 3, and 3 (at least according to numerology) = creativity and self-expression. 3 is a social, friendly, fun-loving number; it has a need to be optimistic; it is often attracted by glitter and ornamentation. It is usually good with words, and if I were to choose one word to describe it I would choose expressive.

In Christian religion, we have the three wise men, three persons in the Trinity, Jesus rising on the third day, and Saint Peter denying Jesus three times. Buddhism, Taoism and even Wicca, have the concept of either three actual deities or one deity composing three different parts.

Three is considered a magic number. There are fairy stories about three bears, three little pigs, three billy goats gruff, as well as three wishes and/or three difficult tasks. We all know that there are three sides/angles to a triangle and that the first and second numbers added together equal three (1+2=3). With one being a masculine number and two the feminine component, three is often looked upon as the child.

The colour associated with three is yellow.

Some books with three in the title are:

Three Lives by G. Stein

The Three Musketeers by A. Dumas

Three Loves by A.J. Cronin

Three Faces of Mourning by S. Akhtar

Three Men in a Boat by J.K. Jerome

Three Sisters by A.Chekhov

Three Guineas by V. Woolf

We are overwhelmed with information about places we must visit, things we should see and experiences we should not miss, but there is not as much written about places we should not visit and experiences that it might be best to avoid.

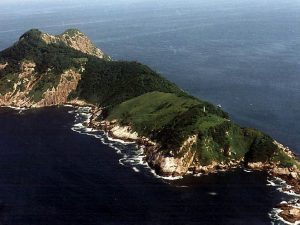

For example: Ilha da Queimada Grande (or Snake Island).

This small island in the Atlantic Ocean belongs to Brazil, is about thirty kilometres to the east of the South American continent, and boasts a lighthouse, which is managed by the navy. At one time (thousands, if not millions, of years ago), it was actually part of the mainland, but with changing sea levels it became an island and, in doing so, trapped a particular snake, the golden lancehead pit viper (or Bothrops insularis). The snake adapted quickly to its new, restricted environment and multiplied exponentially – some people estimate that there is now one snake for every square metre. Added to this is the fact that the golden lancehead pit viper is also extremely venomous, which means that tourist trade to the island is somewhat hampered; in fact, it does not exist.

The snake is protected, and the island has been closed to the public in an effort to protect the snakes from poachers. The closure is also a measure to protect would-be tourists from experiencing a sudden end, not only to their holiday but, more importantly, to life itself. Once or twice a year, a small contingent from the mainland visits the island with a doctor in tow (snake bites can cause internal bleeding, kidney failure and, ultimately, death) in order to check the lighthouse. The only other people visiting the island are researchers who, like the naval personnel, take all necessary precautions against snake bite.

Probably not a place that we are going to regret not seeing, but it is interesting to know that it exists – a small speck in the the Atlantic Ocean.