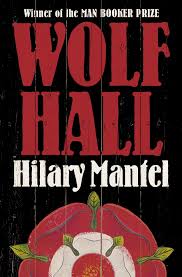

Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel, UK, 2009

This is an amazing book: Mantel’s research is overwhelming to say the least, and the book is filled, not only with facts and historical characters but also with hundreds of small incidental details that set the book well apart from many other books on the subject.

The main subject is Thomas Cromwell and the period is early sixteenth century. The story is well known – there are few surprises in store. The book looks at Cromwell’s relationship with Henry VIII and the men at the top of the power pinnacle. It describes Cromwell’s rise to power; it outlines his thoughts, his anxieties, his hopes; it hints at what is likely to happen sometime in the not-too-distant future.

The book is not only well researched it is also well written. My only comment would have to be Mantel’s unusual use of the third-person singular male subjective pronoun. She uses ‘he’ as a substitute for Thomas Cromwell, and she uses it in many cases where ‘he’ grammatically should be referring to another person – for example, the person speaking or being spoken about, not necessarily Thomas Cromwell. Initially, I found this extremely confusing; however, after one hundred pages or more I accepted that this is possibly one of the ways Mantel keeps Cromwell front and centre at all times.

Wolf Hall turns many other histories of Thomas Cromwell on their head, breaking through the wall of assumed facts to the man behind. He isan ambitious man, but he is also intelligent and, in many instances, compassionate. The unlikeable character, as portrayed in other descriptions of the period, is not to be seen. Instead, the reader is very aware of Cromwell’s propensity to balance situations and, at all times, to be several steps ahead of the scheming nobles surrounding him – not unlike a game of chess. Cromwell is adept at what he does, but even he knows that the complicated dance steps he must master may eventually trip him up.

The book gives the reader an insight into Cromwell, the man, as well as a more sympathetic understanding of the king himself. King Henry, the man who cast off two wives and executed two others, was also, if we are to believe Mantel, thoughtful, if somewhat easily led. Henry became simply a pawn in the hands of the much more powerful nobles all of whom were ambitiously vying for more power, more wealth and more status. He was even an unsuspecting pawn in the hands of Anne Boleyn, a manipulative, power-hungry woman who, in turn, was the product of her very obnoxious family.

In the twenty-first century it is no longer possible to know with conviction what these people from the sixteenth century were really like and/or which version of the period contains the greatest percentage of truth. Nevertheless, I feel that, on the whole, Mantel has presented a number of different perspectives (historically correct or otherwise), which manage to render the main characters in this story more human, if not always as humane as we would like.

Photo of Hilary Mantel from huntspost.co.uk