Diane’s Newsletter January 2018

Mercy

Mercy, writte n in 2007 by the Danish author Jussi Adler-Olsen, is a very well-balanced thriller, switching as it does between the victim, Merete, and the detective, Carl Mörck. At the beginning of the book, Mörck is going through a very rough patch, having been involved in an incident where one of his colleagues died and another was seriously injured, and he lacks the confidence to return to his job as senior detective.

n in 2007 by the Danish author Jussi Adler-Olsen, is a very well-balanced thriller, switching as it does between the victim, Merete, and the detective, Carl Mörck. At the beginning of the book, Mörck is going through a very rough patch, having been involved in an incident where one of his colleagues died and another was seriously injured, and he lacks the confidence to return to his job as senior detective.

As the horror of Merete’s situation (without giving away too much, she is confined in a very small and unbelievably horrible place) becomes gradually apparent, the reader is at times a step ahead of the detective, at times miles behind.

Like a painting, Mercy is built up in layers, each layer giving a little more information, but at the same time adding more anxiety to the overall story. The ending is, as expected, extremely dramatic. A great read if you are looking for something that will remove you from reality for a few hours.

Also published as The Keeper of Lost Causes, the book was made into a film in 2014 (The Keeper of Lost Causes).

Mona Lisa

Most people probably know that Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (Italian: La Gioconda) is a painting, not an expensive type of Italian delicacy or someone’s ex-girlfriend. But how many are aware of the drama and intrigue surrounding the painting?

To start with, no one is completely sure who the lovely lady in the painting is supposed to portray. Is it Lisa del Giocondo (maiden name Gherardini)? Is it da Vinci’s Mum, Caterina? Or is it da Vinci himself? Unless Leonardo had some very strange fantasies regarding himself, I cannot imagine the Mona Lisa as a self-portrait, and, regarding the mother theory, Catarina died in 1495, which meant that the portrait would have had to have been painted entirely from memory.

No doubt some of you are thinking that the name is a dead giveaway and that the subject of the painting has to be Lisa del Giocondo. Unfortunately, it is not all that simple: the painting did not receive the name Mona Lisa until three or four decades after Leonardo’s death, and it is quite possible that Leonardo’s name for the painting was Mrs Gherardini, Mum or even Me. At the moment all bets are off the table, and I am sure that the Louvre would be eternally grateful to the person who solves the mystery.

In the meantime, I am going to assume that Mona Lisa and Lisa del Gherardini are one and the same. Lisa was born in Florence in the latter part of the fifteenth century, married young (as was the custom) and had six children. Her husband, very much her senior, was a successful business man, and, as the story goes, he commissioned Leonardo to paint his wife’s portrait. It is at this point that things begin to get a little confused: some sources say that the commission was agreed upon in 1502 or 1503; while others put the date as late as 1519. Given the fact that Leonardo died in May 1519 (67 years of age) it is difficult to believe that he was able to accept the commission and actually finish the painting in less than four months (although, let’s face it, he was a very smart man). It is more likely that the painting was commissioned around the beginning of the sixteenth century but that it was not completed until 1519.

For the first three hundred years of its existence, give or take a few years, the Mona Lisa was hidden away in private collections, and it was not until 1797 that it was put on permanent public display at the Louvre in Paris.

When it first appeared in the Louvre it caused a sensation. Crowds of people put a visit to the Louvre at the top of their ‘to do’ list, and adoring admirers covered the floor before the painting with flowers and love poems. The written adulation has continued, and the Mona Lisa is the only painting in the Louvre that has its own letterbox to cope with the consistent deluge of love letters. On a darker side, two admirers found the emotion generated by the painting too much: one threw himself from the top of a four-storey building, and another love-sick suitor actually shot himself in front of the portrait.

So what is it about the painting that can cause such excitement? It is only small (77×54 cm); it is painted on board, not canvas; it has around thirty layers of paint; it utilizes an imaginary background, which, at the time, was a completely new concept; and, of course, in the centre of the painting there is the Mona Lisa herself (or himself, depending on which version you accept). Some suggest that da Vinci simply wanted to create a sense of harmony, using a fantasy background and a beautiful woman; others suggest that he was depicting the ideal woman; while still others believe that via the smile he was portraying the mystery and the inaccessibility of the soul. As anyone who has looked at a reproduction of the Mona Lisa (or the real thing), it is the ambiguous smile that is the focus point. Is she happy or sad? Is she looking at you or past you?

No matter how the painting is interpreted, it is worth a lot of money – around 100 million Australian dollars. Also it belongs to the French people, so there is no question of its being either bought or sold. Consequently, it is little wonder that the painting has its own room at the Louvre where it is protected by bulletproof glass. The glass screen was erected in 1956 after two random attacks – the first with acid and the second with a rock. Thanks to the screen, the painting remained undamaged after an attack with spray paint in 1974 and a further attack in 2009 when a disgruntled Russian, who had been denied French citizenship, pitched a mug at it.

Apart from the dramas involving love-sick admirers and sick non-admirers, there has also been drama of another kind: theft. In 1911 the painting was suddenly stolen, and people visited the Louvre in their thousands to leave flowers, letters of condolence or simply to gaze at the spot where the famous painting had once hung.

Suspects, including the artist Picasso and the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, were rounded up, questioned and let go. Suspicion had fallen on Picasso because he was known to have bought stolen pieces of art, and Apollinaire had once said that the painting should be destroyed. (Why did he say such a thing? I have absolutely no idea). The Louvre placed a reproduction of the Mona Lisa in the place where the painting had been hanging, which only made visitors even more aware of what they had lost, and eventually a new, different painting was hung in the same spot.

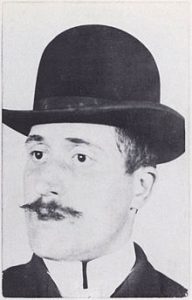

There were a number of reported sightings of the painting that led nowhere. Then in 1913, an Italian, Vincenzo Perugia, who had worked at the Louvre, was caught when he attempted to sell the painting to an art dealer in Florence. He was either very stupid or else he was sick and tired of being constantly on the run. He confessed that he had stolen the painting because, as far as he was concerned, it belonged in Italy and not in France. From his photo he appears to have been a small man, and, although the painting with its backing and glass case would have weighed almost 100 kilos, he insisted that he alone was responsible for the theft. At his trial he was given a seven-month sentence, but as he had already spent that amount of time in gaol he was able to walk free. The painting then did a tour of Italy before finally returning to the Louvre. Something for which the Italians should probably thank Perugia.

Many years later a man calling himself Marquis of the Vale of Hell told an American reporter that it was he who had masterminded the theft, which had been carried out by three men. The Marquis had intended to make forgeries of the painting and then sell them on to collectors for a great deal of money. At the Marquis’ insistence the information was kept secret until after his death, but whether or not the story was actually true is anyone’s guess.

On the positive side, the theft did much to put the Mona Lisa front and centre, and by the time the painting was found and restored to the Louvre it had become an art icon.

Leonardo may have begun the painting in Italy, but he was still working on it when he moved to France (probably around 1515 or 1516) at the request of King Francis I. It is, therefore, possible that there is some truth to the story that he spent twelve years perfecting Mona Lisa’s smile. Although the painting was most likely a commission, Lisa’s husband got absolutely nothing for his money, and when the portrait was finally finished Leonardo gave it to the king. It hung in the palace at Fontainebleau for more than a century, before being moved to Versailles. When Napoleon came to power he kept the painting in his private quarters.

As well as being appreciated as a great work of art in itself, the Mona Lisa has inspired many other creative people, among them artists, film-makers and, not least, song writers. An example from this last category is the song “Mona Lisa” (Ray Evans and Jay Harold Livingston) from the 1950s, which became very popular after being recorded by the jazz singer Nat King Cole.

Mona Lisa, Mona Lisa

Men have named you

You’re so like the lady with the mystic smile

Is it only ’cause you’re lonely

They have blamed you

For that Mona Lisa strangeness in your smileDo you smile to tempt a lover, Mona Lisa

Or is this your way to hide a broken heart

Many dreams have been brought to your doorstep

They just lie there, and they die there

Are you warm, are you real, Mona Lisa

Or just a cold and lonely, lovely work of art

References: Great Artists, Colour Library Books, 1994; Wikipedia; http://leonardodavinci.net; Britanica; http://mentalfloss.com/; The Crimes of Paris: A True Story of Murder, Theft, and Detection, Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler, 2009

Images: Wikipedia

Guest Post: Mikaela

“What would the title to your biography be?”

“If you could have a dinner party with any four people, living or dead, who would you choose?”

I was recently asked these questions in the context of starting a new job, these being prompts to help the whole team get to know each other and open up conversations that might not arise naturally at work. Aware that this was an opportunity to make a lasting first impression, in a new professional setting, I anguished. How could I possibly sum up who I was, or at the very least, introduce myself to a group of new coworkers through a limited selection of historical figures and a few words to self describe? How much of my personal story was I willing to offer? How would my responses be perceived, without the conversation they were meant to spark?

Okay, clearly I was overthinking it. In the aftermath of many New Year Resolutions, both broken and kept, I feel a particular sensitivity to my identity.

Identity is a funny thing: we are who we are, but we are different people in different contexts. We are so attached to our own perception, and often we forget that we are dynamic part of the culture we inhabit. Any label you place on yourself you can certainly recall a time you were not that way. Have you ever invited friends together from separate social circles and had that moment when worlds collided? Perhaps you noted the shift in yourself between your different personalities, or recognized it in your friends demeanor?

In my instance, I struggled because I lacked half of the equation to the dynamic. This was my opportunity to renew my professional self, but without an understanding of this new community I would be joining, I could not predict who I would be to these people. And partially, I didn’t understand who I wanted to be yet, still hoping the New Years Resolutions will “happen”.

In the end my answers were fine, fairly representative of me at the present, and somewhat interesting (I hope!) enough to inspire a few conversations. They did not paint the whole picture of me, and while my responses may shape the impression my colleagues have of me, I’m sure working with them over the next few weeks will quickly reposition who I am to them. But I did find value in the exercise. I will try to practice the process of self-reflection, appreciate the role of culture in my identity, and be at peace with the changing landscape of who I am at the moment.

Magenta

![]()

Magenta is that colour that is not pink, not purple but somewhere halfway between blue and red. Its complementary colour is green, and in printing it is used, together with yellow, black and cyan, to make all other colours.

It was discovered in 1859 when a French chemist, François-Emmanuel Verguin, mixed aniline dye with carbon tetrachloride. No doubt delighted with his discovery, he promptly patented the colour, calling it fuchsine (fuchsia).

The following year, 1860, two British chemists, Nicolson and Maule, produced an almost identical colour and called it roseine, but after the French victory against the Austrians at Magenta in Italy, they changed the name to magenta. The colour became an instant success.

Reference: Wikipedia