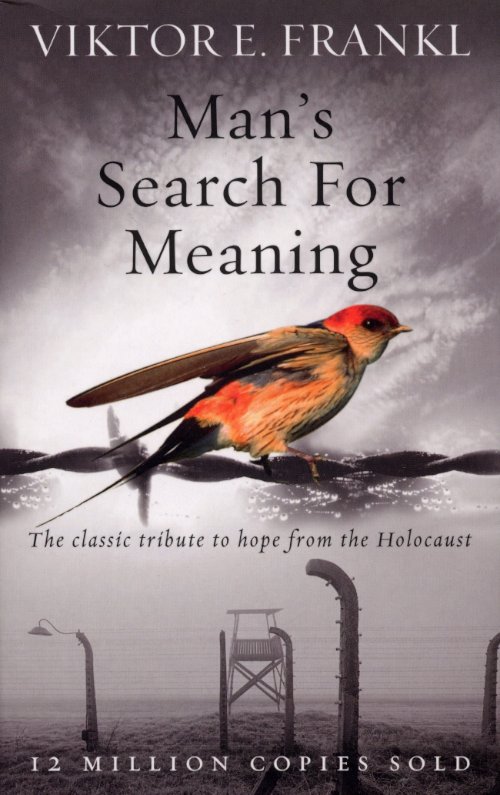

Man’s Search for Meaning, Viktor E. Frankl, 1946

Viktor Frankl, who founded the third school of Viennese psychotherapy, that is to say logotherapy (the search for a meaning in life as a central motivational force), was sent to one of Hitler’s concentration camps in 1942, an ordeal he barely survived. His own experience coupled to the experiences of others confirmed his theory that it is essential that we are able to isolate a meaning with our life. A meaning can be found in a specific work or deed; it can be found in our love for another person; or it can be found in facing and accepting a fate we cannot change. He did not accept that the meaning of life was bound up with a quest after pleasure or power. Putting his own beliefs into practice, Frankl survived by focusing on being reunited with his wife (though he had no idea whether she was still alive) as well as visualizing himself, after liberation, putting forward his theory of logotherapy.

He also managed to help many of the other camp inmates, many of whom could see no point in clinging to a life that was so pointless and cruel. By finding a meaning beyond the confines of the camp (a loved one or an occupation that was waiting for them somewhere) or an acceptance of a fate that they could not change, many of these men were able to survive and so experience liberation. The meaning that each individual attaches to life will be different; as Frankl points out, there is no one, abstract meaning of life: Everyone has his own specific vocation or mission in life to carry out a concrete assignment which demands fulfilment. Therein he cannot be replaced, not can his life be repeated.

Frankl’s understanding that any group of people is a mixture of both decent and indecent individuals brought him a certain amount of criticism, especially in USA where he lectured as visiting professor. It was expected that, having endured three years in Nazi concentration camps, he would be anti anything and everything German. He knew from experience that a prison guard could be a decent person while many of the Capos (prisoners elevated to guard-like duties) could be both cruel and indecent. His focus was not on the group but on the individual and the meaning that his fellow camp inmates could attach to lives that to an outsider appeared completely hopeless.

Frankl’s book is divided into two parts: the first part is a horrifying account of his experiences in the camps; the second part, entitled Logotherapy in a Nutshell, attempts to explain his theory of meaning in life being the most important motivational force. While the second part is much more technical and reads like a text book, the book as a whole can, and should, be read several times; each reading revealing new perspectives and new understandings of self.

Harold S. Kushner quotes Frankl in the preface to Man’s Search for Meaning: You cannot control what happens to you in life, but you can always control what you will feel and do about what happens to you, which is another way of saying “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”