Levels of Life, Julian Barnes, UK, 2013

From heights close to the moon to the darkness of the Underworld, this is a beautiful book about love, life and death, Barnes writes at the very beginning: ‘You put together two things that have not been put together before. And the world is changed. People may not notice at the time, but that doesn’t matter. The world has been changed nonetheless.’

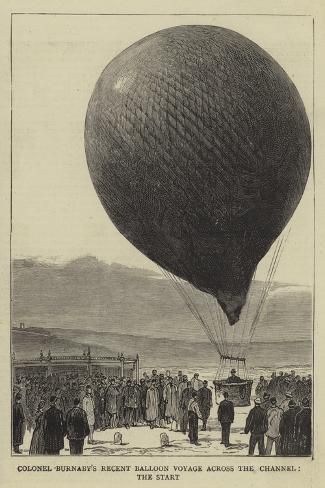

Divided into three parts – The Sin of Height, On the Level and The Loss of Depth – Levels of Life first looks at the early balloonists Félix Tournachon and Colonel Fred Burnaby as they experience the hitherto impossible sensation of observing the earth from on high. In both cases there is the dizzying sense of freedom and the ever-present danger of the balloon catching fire or being blown off course; there were no such things as parachutes. When Tournachon took the first ever photographs of the earth from above – black and white, and not particularly clear – it was he who gave us the possibility of looking at ourselves from afar: ‘he made the subjective suddenly objective.’

The second part of the book traces the love affair of Colonel Burnaby with Sara Bernhardt – a somewhat one-sided attraction where Bernhardt is caught up in the excitement of the moment and Burnaby is looking ahead to a more conventional relationship. ‘You put together two people who have not been put together before: and sometimes the world is changed, sometimes not (…) Together, in that first exaltation, that first roaring sense of uplift, they are greater than their two separate selves.’

In The Loss of Depth, Barnes talks about the death of his wife, Pat Kavanagh, in 2008. They had been married for thirty years. ‘What we did, where we went, whom we met, how we felt. How we were together. All that, “We” are now watered down to “I”.’ He talks about the pain, realizing eventually that it is proof of love and is therefore positive. He talks about loneliness and decides that there are two kinds of loneliness and that the worst kind is never having had anyone to love. An agnostic, Barnes writes about the importance of continuing the conversation, explaining that ‘the fact someone is dead may mean that they are not alive, but doesn’t mean that they do not exist.’

At the end of the book he asks himself if moving beyond grief is actually a fight that can be won or lost, or whether it is simply the universe ‘doing its stuff’. ‘We imagine that we have battled against it, been purposeful, overcome sorrow, scrubbed the rust from our soul, when all that has happened is that grief has moved elsewhere, shifted its interest. We did not make the clouds come in the first place, and have no power to disperse them. All that has happened is that from somewhere – or nowhere – an unexpected breeze has sprung up, and we are in movement again.’

Honest, sad, intellectually and emotionally beautiful, Barnes’ book is like a poem; it can be read many times, and parts of it will remain with you for ever.