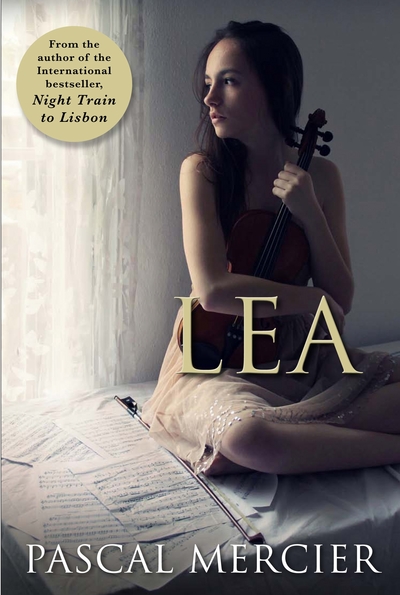

Lea, Pascal Mercier, Germany, 2007 (English translation 2017)

Beautifully written and painfully tragic, this novel is about the unconditional, and at times seemingly unreasonable, love of a father for his daughter.

Martijn van Vliet, a research scientist, and Adrian Herzog, a surgeon who has lost confidence in himself, meet by chance in Saint-Rémy. There are similarities between the two men; they are both from Bern; they are both professionals; they are both single parents – Martijn’s wife died many years ago and Adrian is divorced – and they each have an only child, an adult daughter. Adrian’s relationship with his daughter, Leslie, is not as close as he would like while Martijn refers to his daughter, Lea, in the past tense. Adrian is aware that Martijn is desolate and depressed, perhaps even suicidal, and he offers to drive both of them back to Bern in Martijn’s car. During the car trip, which takes several days, Martijn talks to Adrian about himself and, most of all, about Lea. His words and memories drive the story forwards, sometimes rapidly with a sense of certain doom; sometimes taking detours where time seems to stand still, and where, for a moment, certainty is not all that clear. Divided between Martijn’s narrative and Adrian’s questions and thoughts, the writing is exquisitely managed like a piece of music where every note is important. No word is superfluous; no phrase or image unnecessary.

After the death of Martijn’s wife, Cécile, Martijn is left to take care of their young daughter, but Lea quickly descends into a dark abyss of sadness where no one – not ever her father – can reach her. Then, one day when eight-year-old Lea and her father are passing through Bern railway station, they hear a woman busker playing a violin. Lea is captivated. By the time she and her father arrive home she is already beginning to climb out of the abyss. She asks her father, “Is a violin expensive?”

And so begins Lea’s long wandering towards self annihilation. As she learns to play the violin, she discovers a natural aptitude for the instrument, and the ecstatic response from those who hear her playing is for her like water to someone lost in the desert. Martijn, who had hoped that the violin would have brought them closer, is pushed to one side as Lea, focused only on her goal of being the very best, is prepared to sacrifice everything for the experience.

If only Martijn had not bought his daughter a violin; if only Marie Pasteur, the music teacher, had never become part of their lives; if only Lea had not entered the music competition; if only she had not met David Lévy … But the ‘if onlys’ are all irrelevant: Martijn and Lea have no alternative other than to continue on a predetermined trajectory towards inevitable destruction. For Lea music becomes an obsession, the only way she can function and, perhaps, somehow balance the loss of her mother. For Martijn it becomes the only way he believes he can show his daughter that he loves her. It is a love that forces him to step out of his normal, logical scientific self and make insane and frightening decisions. Throughout the book, the focus is on the father and daughter relationship. Relationships with other people are sketchy, only filling out as they become entwined with the main theme and with the reality of imperfect communication.

Although the ending is bleak (and it is obvious from the beginning of the book that there can be no other ending) there is a sense in those final pages that, in spite of the miscommunication, the obsession, the pain and the many wrong decisions, love is actually the only thing that matters – a fact that, on some level, both Martijn and Lea completely understand.

‘He took her hand. She put up no resistance. Later he felt her head on his shoulder. That opened the floodgates. Wrapped in a clumsy embrace, they both gave their tears free rein.’