Independent People by Halldor Laxness, Iceland, 1934

Covering almost 600 pages, Independent People is not a book to be read in one sitting, and, even if it were possible, to read the book in such a way is not to be recommended. This is a book that has to be digested slowly. Set at the beginning of the twentieth century it is not a happy read: the abject poverty of the lower classes compared with the relative comfort of the ruling classes was definitely not isolated to Iceland, but in Laxness’ book the hunger and the misery is played out against a harsh, cold, unrelenting landscape.

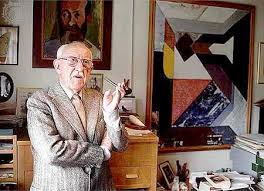

Covering almost 600 pages, Independent People is not a book to be read in one sitting, and, even if it were possible, to read the book in such a way is not to be recommended. This is a book that has to be digested slowly. Set at the beginning of the twentieth century it is not a happy read: the abject poverty of the lower classes compared with the relative comfort of the ruling classes was definitely not isolated to Iceland, but in Laxness’ book the hunger and the misery is played out against a harsh, cold, unrelenting landscape.Born in 1902, Laxness is writing about a period he actually experienced, in the environment where he grew up, and the book exudes a definite feeling of authenticity.I would even go so far as to guess that parts of the book are autobiographical or, at least, semi-autobiographical. In other words, Laxness has obviously referred to his own experiences and to those of people he has known when writing the book.For example, when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1955, he mentioned his grandmother in his acceptance speech and commented on how close she had been to him. He went on to say that she had always stressed upon him the importance of respecting those who hold a lowly position in the world and that he should never ill-treat animals. In the book Bjartur’s mother-in-law says practically the same thing to her grandson Nonni.

Revolving around Gudbjartur of Summerhouses, the book delves into the concept of independence versus the dependence that is the lot of the lower classes. Gudbjartur, or Bjartur as he is called throughout the book, spends eighteen years slaving for the landed gentry so that he might be able to buy his own piece of land and become independent. After an introduction that gives some historical aspects to the story the actual novel begins with Gudbjartur, newly married with Rosa, on his way to take up ownership of his plot of land in an isolated part of northern Iceland.

Revolving around Gudbjartur of Summerhouses, the book delves into the concept of independence versus the dependence that is the lot of the lower classes. Gudbjartur, or Bjartur as he is called throughout the book, spends eighteen years slaving for the landed gentry so that he might be able to buy his own piece of land and become independent. After an introduction that gives some historical aspects to the story the actual novel begins with Gudbjartur, newly married with Rosa, on his way to take up ownership of his plot of land in an isolated part of northern Iceland.Life is not only grim, it is unbelievably awful, and Bjartur’s fixation with being independent means that he cannot, and will not, accept any kind of help from anyone. This attitude did not endear him to me, in fact I found him extremely irritating, and as the story proceeds it is frustrating to see how he hurts those closest to him. Until the very last pages of the book, he seems to be completely devoid of any kind of emotional connection with his fellow man; though perhaps it is to his merit that he does finally let go of his stubbornness and his fixation on independence to be able to experience a deep emotional connection with another human being.

This is an amazing novel, beautifully written and wonderfully orchestrated. The descriptions of the landscape and the climate are so magnificent that I froze through most of the book. A subdued kind of humour acts as a foil to the serious theme of the book while historically it gives a very good picture of the social situation in Iceland in the early part of the twentieth century.

Definitely not a book to be missed.

Photo of Halldor Laxness from Encyclopaedia Britannica