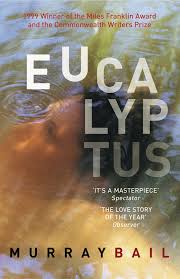

Eucalyptus, Murray Bail, Australia, 1998

An Australian fairytale, beautifully told, Eucalyptus does not follow a set template. Like many of the trees that play a major role in the book, it twists and turns both back on itself and away from itself, leading the reader into places he or she does not even anticipate.

An Australian fairytale, beautifully told, Eucalyptus does not follow a set template. Like many of the trees that play a major role in the book, it twists and turns both back on itself and away from itself, leading the reader into places he or she does not even anticipate.

On the surface, Eucalyptus is the story of Mr Holland, a widower, who buys a property in the far west of NSW and proceeds to plant every known variety of eucalyptus tree. Eventually he is surrounded by more than five hundred different kinds of eucalypts. However, Mr Holland also has a beautiful daughter, Ellen, and he is confronted with the problem of finding a suitable suitor for her. He is a possessive man, and he cannot imagine anyone being worthy enough to marry his daughter.

Like the king in ancient fairytales, Mr Holland decides to set a challenge for those desiring his daughter’s hand in marriage: the man who is able to correctly name all the eucalyptus trees on the property will be the winner. Initially, Ellen is unperturbed by the idea of being married off to a stranger with such a narrow, if admirable, area of expertise. A steady stream of men come and go; many of them do not even manage to name the trees closest to the homestead.

Then a Mr Cave presents himself and as the days pass and he reels off name after name it is obvious that he knows eucalyptus trees just as well as Mr Holland, and the question is no longer if he will win but when.

Ellen had never imagined that such thing could happen: Mr Cave is as old as her father. She retreats into her own cave, hoping for a positive outcome.

Woven into the story of Mr Holland’s challenge and Mr Cave’s extraordinary knowledge there is a third person – a story teller. We do not know his name, but he appears among the trees when Ellen is out walking. His stories are varied. Many of them are sad. Most of them concern a woman. Many of them finish abruptly, leaving the reader (and no doubt Ellen) wondering: But what happened next?

Bit by bit Ellen falls in love with this stranger.

Comprising an amazing knowledge of eucalypts, Eucalyptus is not only one fairytale but many, and I found myself wondering about connections and linked threads. Perhaps, in the end, the stories are like the eucalypt itself ‘. . . apart, solitary, essentially undemocratic. . . ‘ (page 16), and perhaps it is not so much the connections but the experience of simply being.