Diane’s Newsletter 17th July 2018

is the 16th letter of the English alphabet, and most words in English that begin with P are of foreign origin: Latin, Greek, French.

P can also be used as:

the symbol for penny (or pence)

to denote softly in music (piano:Italian. softly, quietly)

the symbol for pico- (prefix indicating 10−9 as in ps, picosecond)

the symbol for pressure in Physics

Various forms of P can be used as follows:

₱: Philippine peso sign

℘: script letter P

℗: sound recording copyright symbol

♇: symbol for Pluto

ꟼ: Reversed P – used in ancient Roman texts to stand for puella (girl)

In Numerology P is an inexpressive thinker. People whose names begin with P are often reserved and introspective, sometimes even secretive. They usually work best alone, and although they feel deeply they are not necessarily comfortable with their feelings. Such people are often intellectually inclined; they think a lot and may be interested in meditation and related practices. They enjoy analysing ideas and situations and they are usually philosophical. On the negative side they may lack determination and willpower.

The colour associated with P is violet.

Sources: wikipedia, encyclopedia.com and Numerology: The Complete Guide Matthew Oliver Goodwin

Pasta Primavera

Ingredients

250g dried farfalle pasta

2 zucchini, ends trimmed, halved lengthways, thinly sliced diagonally

1 bunch asparagus, woody ends trimmed, cut into 2cm pieces *

250g snow peas, stringed, trimmed and thinly sliced lengthways

4 yellow squash, ends trimmed, thinly sliced

300ml cream

1 tablespoon mustard

1 tablespoon finely shredded lemon rind

2 garlic cloves, crushed (or chopped finely)

1/4 cup finely shredded fresh basil

Mixed salad leaves, to serve

* When I decided to make this recipe I could not get hold of asparagus anywhere, so I used green beans instead. Trim the ends and cut into 2cm pieces.

Method

1

Cook the pasta in a saucepan of salted boiling water until al dente. Add the zucchini, asparagus, snow peas and squash and cook for 2 minutes or until snow peas are bright green and tender crisp. Drain and return to pan.

2

Meanwhile, combine the cream, mustard, lemon rind and garlic in a frying pan over high heat. Bring to the boil. Reduce heat to low and simmer, stirring, for 2 minutes or until the sauce thickens.

3

Add the cream mixture to the pasta and toss until just combined. Stir in the basil and season with salt and pepper. Serve with mixed salad leaves.

Recipe and image above from Taste Magazine (Australia). Image below: Diane

My comment: This is a really great recipe, and I highly recommend it. As you already know, I used green beans instead of asparagus, and they worked particularly well. Make sure that you have all the vegetables prepared before cooking the pasta. Also, I used mustard seeds and not prepared mustard. Once you add the vegetables to the pasta you may need longer than 2 minutes for cooking (and you may need to add extra water). Can be served on its own with mixed leaves and/or with vegetarian rissoles.

My comment: This is a really great recipe, and I highly recommend it. As you already know, I used green beans instead of asparagus, and they worked particularly well. Make sure that you have all the vegetables prepared before cooking the pasta. Also, I used mustard seeds and not prepared mustard. Once you add the vegetables to the pasta you may need longer than 2 minutes for cooking (and you may need to add extra water). Can be served on its own with mixed leaves and/or with vegetarian rissoles.

The Pindus* Horseshoe Walk

(*also known as Pindos and Pindhou)

I was looking for a hike that begins with P, and, of course, the ones that first came to mind were the Pacific Crest Trail and the Pacific Northwest Trail, but I decided that it could be exciting to look at a less well known hike.

The Pindus (Pindos, Pindhou) Horseshoe walk is in the Epirus region in northern Greece, just south of the border with Albania. The track measures 58 kilometres and it takes 3-4 days to complete.

The walk is circular (horseshoe) and follows old mule tracks. It begins and ends in Monodendri (1060 metres above sea level) where there is a beautiful, but abandoned, monastery – the Monastery of Saint Paraskevi. The monastery was built by a local lord at the beginning of the fifteenth century in thanksgiving for his daughter having been saved from some dreadful illness.

From what I can gather the walk is reasonably challenging, with the maximum altitude around 2,500 metres. The Vikos Gorge is supposed to be the steepest in the world. Add to this forests, amazing views, plateaux, wildflowers (summer), high peaks, low valleys and little stone villages (which are special for the area), and the walk is an experience not to be missed.

Camping is possible; however accommodation can be found in the beautiful villages. Water is not a problem, and, although some articles say that it is okay to drink without boiling/filtering, I would probably not drink it without treating it first, especially in the lower areas of the track. The track might be fairly obvious, but it is suggested that anyone setting out on the walk should pack a reliable topographic map.

Images:

Pindus Mountain: wikipedia, visit Greece and Oddizzi

Vikos Gorge: Max Pixel

PASSPORTS

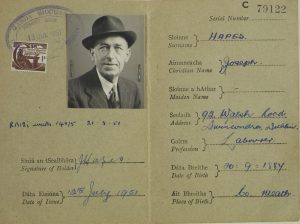

Most of us have used a passport or, if we haven’t, we know someone who has. Up until 3rd September 1912, passports were not compulsory, but, with WWI looming, countries saw a need to protect their borders, and very simple (in many cases, one page) passports came into being.

It is believed that the word passport was first used on a mediaeval document, which allowed the bearer to ‘pass through the gate’ of the city or to move from one town to another; however, some people believe that the word ‘port’ refers to maritime ports (allowing passage from one port to another) and not to the French word porte:gate. No matter which of these explanations is correct, both of them refer to a person being permitted to pass from one place to another.

The very first reference to anything that resembles a passport is from around 450BC when King Artaxerxes I of Persia gave one of his officials, Nehemiah (who had been given the job of rebuilding the walls of Jerusalem), a letter to allow him to travel safely through several lands to Judea.

In mediaeval times, as well as the document allowing safe passage through gates or between towns and ports, there was also a similar system in Arabia. The bara’a (which was actually a receipt to show that taxes had been paid) could be used to allow holders to travel throughout the Arabian Caliphate.

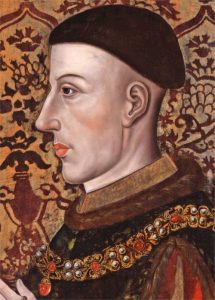

At the end of this period, in the early 1400s, King Henry V (or perhaps it was one of his advisers) came up with the idea of issuing travellers with a document that could prove who they were when they were travelling in foreign lands – this, in effect, describes our modern passport. According to one information source, foreign travellers did not have to pay for their document (or passport) while English travellers were not afforded the same consideration.

At the end of this period, in the early 1400s, King Henry V (or perhaps it was one of his advisers) came up with the idea of issuing travellers with a document that could prove who they were when they were travelling in foreign lands – this, in effect, describes our modern passport. According to one information source, foreign travellers did not have to pay for their document (or passport) while English travellers were not afforded the same consideration.

It is perhaps of interest that since 1794 there is a record of every passport issued in the UK, and that up until 1858 they were actually written in French. After 1858 the UK passport was not only written in English, but it also gradually assumed the role of an identity document. Even so it was not required for international travel until WWI.

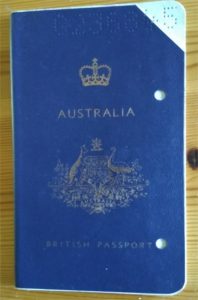

Up until the 1960s not many people in Australia had a passport, probably because travel was not as popular or as affordable as it is today. Today it is calculated that about half of Australians own passports (compared with about one third of Americans). Australians who had a passport issued before 1967 would have noticed that it was a British Passport as Australians were still considered British subjects. Moreover, until 1983 an Australian woman applying for a passport could only do so if her husband gave his permission and signed the application form.

Up until the 1960s not many people in Australia had a passport, probably because travel was not as popular or as affordable as it is today. Today it is calculated that about half of Australians own passports (compared with about one third of Americans). Australians who had a passport issued before 1967 would have noticed that it was a British Passport as Australians were still considered British subjects. Moreover, until 1983 an Australian woman applying for a passport could only do so if her husband gave his permission and signed the application form.

Passports from last century are usually filled with entrance and exit stamps from different countries, and looking through these passports can be a way of remembering places and events; however, with the advent of the new century and the expansion of electronic data collection, stamps have almost become obsolete, which is a pity. While doing research for this article, I came across Siddhant Gupta who is suggesting a Passport Card, which is not only a passport but also an identity card, licence, bank card, medical record. . .

Even if we have not yet realized Siddhant’s dream of a simple passport, passports have undergone some remarkable security changes over the past couple of decades. Biometric data (photographs, iris patterns and fingerprints), watermarks and digital signature data make modern passports exceptionally difficult to forge, especially given the fact that they usually have to be approved by an unemotional, neutral machine.

We may well complain about the cost of a passport (an Australian passport, valid for ten years, costs $282); however, at the end of the eighteenth century, when the French Revolution was at its height, a passport issued in England for travel to France could cost as much as six pounds, seven shillings and sixpence, which in present-day money equals more than one thousand Australian dollars.

We may well complain about the cost of a passport (an Australian passport, valid for ten years, costs $282); however, at the end of the eighteenth century, when the French Revolution was at its height, a passport issued in England for travel to France could cost as much as six pounds, seven shillings and sixpence, which in present-day money equals more than one thousand Australian dollars.

In essence, the idea between the modern-day passport and the documents of mediaeval times (and even the letter written by King Artaxerxes I) is the same: they all request, on behalf of some authority, that the holder or the bearer of the passport (or letter) should be allowed to pass freely and be afforded assistance and protection if needed.

Images: wikipedia

Reading matter: wikipedia, The Guardian, The West Australian

Guest Post

Vad är konst?

Per-Arne, Sverige

Är detta verkligen konst har säkert många frågat sig inför något obegripligt. Själv har jag arbetat med fotografi och film sedan slutet på 60-talet. Under merparten av denna tid har fotografi inte betraktats som konst och därför har jag inte sett mig själv som konstnär. Men nångång på nittiotalet skedde en förändring, fotografi hittade plötsligt in på de fina konstgallerierna och det betalades stora pengar för foton på de fina auktionsfirmorna.

För mig har frågan blivit aktuell då jag fått möjligheten att ställa ut fotografier på galleri. Jag undrar om mina enkla bilder kan kallas för konst. Men om det inte är konst, vad är det då? Efter att ha funderat lite så kom jag på att det kanske då skall kallas för illustration. En illustration är något som man brukar se tillsammans med en tidningsartikel. En nyhetsbild på en aktuell händelse är knappast konst utan mer en illustration. Det är nog de flesta överens om. Men om samma bild visas på ett konstmuseum eller galleri, har den då övergått från illustration till att bli ett konstverk?

När man ser en konstutställning så brukar det konstnärens CV finnas tillgängligt. Ofta ser man då en lista på olika konstutbildningar som denne har gått. Då frågar man sig att det kanske är ett krav för att ens verk ska få kallas för konst att man måste ha en gedigen konstutbildning bakom sig? Det har inte jag, så kanske därför kan mina bilder aldrig bli konst?

Här visar jag ett fotografi som visats på ett galleri och du får nu chansen att tycka om detta är konst?

Guest Post

What is Art?

Per-Arne, Sweden

‘Is this really art?’ is something many have asked themselves as they stand, looking at an artwork that is beyond their comprehension. I have worked with photography and film since the end of the 1960s, and for most of this period photography was not considered art; consequently, I have never thought of myself as an artist. However, sometime during the 1990s there was a change – photography suddenly found its way into leading art galleries and it began to attract large amounts of money at some of the best auction houses.

As I am given opportunities to exhibit my photography at galleries the question becomes important for me personally. I ask myself if my simple images can be called art. But, if they are not art, what are they then? After some reflection I decided that perhaps they should be called illustrations. An illustration is something that you often see together with a news article. An image accompanying a current news article can hardly be called art; it is more an illustration. Most would have to agree on that point. But, if the same image is shown in an art gallery does it then suddenly move from being an illustration to being an artwork?

At most art exhibitions the artist’s CV is usually on display with a list of the artist’s various art studies and qualifications, which makes me wonder if a substantial art education is the requirement for one’s creative work being called art. I do not have such qualifications, so does it therefore follow that my images can never be classed as art?

Below is one of my photographs that has been shown at a gallery. You can decide whether or not you would call it art.

2 Replies to “Diane’s Newsletter 17th July 2018”

Dina månadsbrev är otroligt fina. Du kan ju allt “mellan himmel och jord” och är väl förmodligen professor. Det visste jag inte, men det vet jag nu. Fortsätt i hundra år till och gör oss lyckliga. GM

Tack, Gunnar. Jag är glad att du gillar nyhetsbrevet, men jag tror inte att kommer att fortsätta i hundra år till. . . Diane