A Room Made of Leaves, Kate Grenville, Australia, 2020

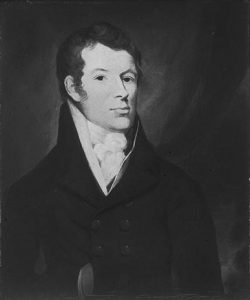

Kate Grenville’s latest book can best be described as fictional history. It follows the life of Elizabeth (Veale) Macarthur from her life as a more-or-less orphaned child in Devon to her life in Sydney and Parramatta as the wife of the insensitive, brutish and unpredictable John Macarthur. Macarthur’s name is now firmly connected to the establishment of the wool industry in Australia; however, Grenville puts forward the likely theory that without Elizabeth’s brains and foresight John Macarthur would have remained a very minor name in the history of Australia.

Kate Grenville’s latest book can best be described as fictional history. It follows the life of Elizabeth (Veale) Macarthur from her life as a more-or-less orphaned child in Devon to her life in Sydney and Parramatta as the wife of the insensitive, brutish and unpredictable John Macarthur. Macarthur’s name is now firmly connected to the establishment of the wool industry in Australia; however, Grenville puts forward the likely theory that without Elizabeth’s brains and foresight John Macarthur would have remained a very minor name in the history of Australia.

Weaving actual historical facts with fictional accounts of events and people, Grenville has created a plausible tale that attempts to get to the very core of the person Elizabeth Macarthur may have been. Nonetheless, aware of the liberties she may have taken with Elizabeth’s story, Grenville writes (in several places): ‘Do not believe too quickly’ – a quote she attributes to Elizabeth.

After Elizabeth’s baby sister and father die, five-year-old Elizabeth and her mother move to the farm owned by her maternal grandfather, but then Elizabeth’s mother remarries and Elizabeth is left on the farm with her grandfather. She probably would have remained where she was had not the Reverend Kingdon, whose daughter Bridie was friendly with Elizabeth, suggested that Elizabeth move to the vicarage.

Elizabeth is given a sense of family and a good education and, in her early twenties, meets Ensign John Macarthur, ‘ an ugly cold sort of fellow’. Life very quickly takes a turn which Elizabeth had not been anticipating, and before she has had time to fully comprehend what is happening, she is married and is on her way to Sydney, Australia. John Macarthur may have been unstable and incompetent, but he is also a man of ambition, and in England’s southern colony he sees a chance for both recognition and advancement.

Sydney was doubtlessly not what Elizabeth had expected, but she turns the experience into something positive, no doubt motivated by something an innkeeper’s wife said to her before she left England: ‘… A woman can do many things, but she has to bide her time.’

Beautifully imagined and written, the book weaves together aspects of life in the starkly male-dominated colony with a few scattered threads of emotional sensitivity and intellectual awareness as personified in, for example, John Dawes, the astronomer who shows Elizabeth the understanding and affection she is lacking in her marriage. While the actions of the Europeans – both positive and negative – may be seen as the weft of the weave, the cruel and unjust treatment of the Aboriginal peoples is the warp, attempting to hold the fabric together.

It is possible that some who have read earlier books by Grenville may resent her re-visiting themes, such as the theft of Indigenous land, that are central to her other books; however, writing about a particular period in Australia’s history, Grenville is necessarily limited by the realities of that period.

A Room Made of Leaves is a tribute not only to Elizabeth Macarthur but to women everywhere.